Ten years have passed since my Type 1 diabetes diagnosis, and as I get to know myself more as a person with diabetes, I have learned that to do what I’ve always loved to do and to try new things is possible, but both require more planning than in the past.

Managing diabetes requires me to regularly consider what I need to live every day regardless of what I am doing or where I am. I have to deliberate, prepare, and strategize before heading off into the woods and away from the safety of home and a comfortable routine. What did I forget? What if I my CGMS stops working? What if my insulin gets hot? What if I run out of glucose gels?

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent="yes" overflow="visible"][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type="1_1" background_position="left top" background_color="" border_size="" border_color="" border_style="solid" spacing="yes" background_image="" background_repeat="no-repeat" padding="" margin_top="0px" margin_bottom="0px" class="" id="" animation_type="" animation_speed="0.3" animation_direction="left" hide_on_mobile="no" center_content="no" min_height="none"]

Once I count and enter the number of carbohydrates I am going to eat; the glucose meter suggests a dosage (called a bolus) which I can accept or alter as needed. When I decide to be active, I can choose a higher or lower baseline insulin rate depending on my activity level (it’s all guesswork). This system functions as my personal external electronic pancreas, and it’s helped me to live a more flexible life than when I was on 4 to 6 shots a day.

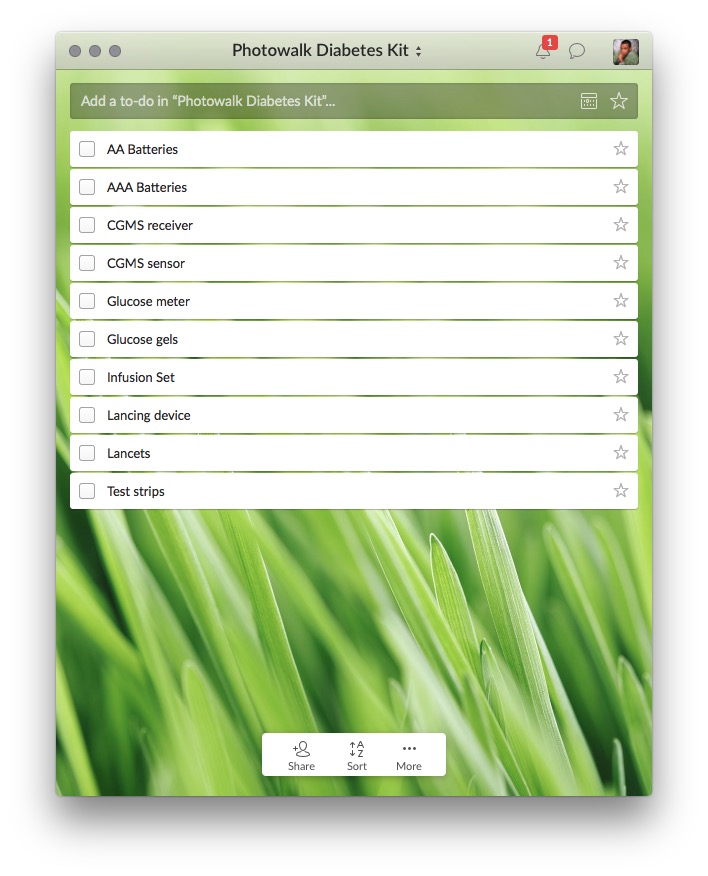

Before I go into the woods to hike or take photos, I run through the list of things I would need. I’ve learned that the added exertion of walking in the woods or long walks around a large city causes me to burn glucose at a faster rate, and it takes me a while to get enough carbohydrates in my system to sustain my activity.

During one recent hike this past spring I downed two 22g glucose gels just to keep my blood sugar high enough to walk back to my car. I brought what I thought was enough glucose tabs to handle possible hypoglycemia and adjusted my insulin based on an estimate of excursion. 30 minutes into the hike and my blood glucose dropped, and the devices started beeping. I used up all the glucose tabs, and things did not improve. Thank goodness my friends had snacks.

The other thing I have to consider is that there is no cell signal out in the woods. If I have a hypoglycemic episode (undetectable without my bio-hardware) or a diabetes device failure, having someone with me provides added comfort in knowing there is someone who can help me if I need it.

T1 (autoimmune) diabetes is not something about which a patient can escape thinking. But over time I’ve developed a go-to checklist, with my medical supplies listed next to my photography essentials, diabetes no longer gets all the attention when I’m planning.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Along the trail were some abandoned buildings.

I take my husband (also diabetic) birding and he has a nasty habit of forgetting his glucose tabs and snacks. I can tell before he does that he is getting low. He uses an insulin pen.

Hi Sherry. Thanks for sharing. PWD need people around us to help, especially when even our best plan fails.

Perhaps your husband is forgetting his glucose tabs because he dislike the taste and texture. Has he tried TRANSCEND 15g Glucose Gels?

Thanks. I'll have him get him.